In this first installment of Universitour, Karina discovers an important part of Canada’s historical culture with guiding help from a totem pole

Late December morning, towards the end of 2021, I walked down the paved street around the University of British Columbia (UBC) campus in Vancouver. It was the day when days were shorter, and the streets were covered with thick glistening snow. The campus was still empty, and nobody walked around; this blatant mask that perversely told the people that the new term had not started yet. After fifteen minutes of walking, I stopped in front of a standing tall totem pole near the Forest Sciences Centre building. That was the first time I saw an actual totem pole. A little bit further to the right side of the totem pole was a big wooden gate delicately carved. Coming from a line of wood carvers (though it ended at my Grandpa), I was captivated by the intricacy of the craftsmanship. I also remember reading about Indigenous people on the wooden gate. Still, back then, I didn’t know how significant it was.

Indigenous, Indian, Aboriginal, and First Nations

Indigenous people have lived in North America for hundreds of years before the arrival of Europeans in America1. Other terms that are used to address them are Indian and Aboriginal people. In Canada, the term that is commonly used has changed to First Nations people.

Canada is a country that is colonised, while some said dispossessed, from the First Nations people. About 95% of British Columbia is on unceded territories of First Nations2. The word “unceded territory” means that First Nations did not legally sign away their lands to Britain or Canada. Despite having a wide area of land, First Nations represent only 4.9% of the total population in Canada3. Through treaty-making between the federal government of Canada and the First Nations, the government is permitted to intervene in managing First Nation lands as their guardians4. As a result, many buildings and public facilities are built on First Nation lands, including the UBC campus.

What does it have to do with UBC?

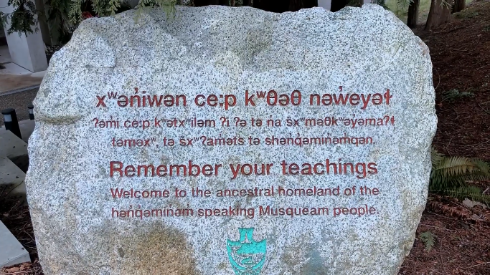

UBC Vancouver is situated on the Grey Point peninsula. At a glance, the campus offers a scenic panorama with snow-capped mountains on the north side and a turquoise sea stretching from the west to the north side. This stunning location has been part of the Musqueam territory for centuries.

In short, Musqueam, or Xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, is an Indian Band (not a literal band. More like a body of Indians in one particular area of Canada) that has lived in the territory that we now know as Vancouver and the British Columbia area for thousands of years. Nowadays, members of the Musqueam tribe live on a small portion of their traditional territory, known as the Musqueam Indian Reserve, located south of Marine Drive near the mouth of the Fraser River. However, it has to be truly underlined how they are the original settlers of the Vancouver area.

UBC and Musqueam’s formal relationship began with the Treaty, Lands & Resources department of Musqueam reaching out to UBC. Later, the relationship was formalised by the Memorandum of Affiliation in 2006. Thus, land acknowledgements are created as an appreciation, commitment, and recognition to First Nations. In UBC Vancouver, we can hear a land acknowledgement being read to respect the Musqueam as the owner of the land. Listening to the land acknowledgement read in a class or an event is not uncommon. A similar thing goes for Vancouver, Toronto, Edmonton, and other cities in Canada that acknowledge some other First Nation groups.

Apart from the land acknowledgement, UBC has a massive strategic plan to respect the Musqueam territory, learn the history of the land, and engage with the community. Programs such as Musqueam 101 course, Musqueam language course, naming student housing based on Musqueam language, raising the Musqueam flag at UBC, and Musqueam art installations across the campus are examples of UBC’s initiatives in acknowledging Musqueam territory.

Reconciliation Pole

One of the most prominent art installations is the Reconciliation pole which is no other than the totem pole that I saw on that particular December morning in UBC. The pole was commissioned by Michael Audain, a Canadian philanthropist, and carved by a Haida carver, 7idansuu (Edenshaw) James Hart, alongside other assistants. It was installed in 2017 to symbolise truth and reconciliation regarding the dark history of Indian residential schools. Indian residential schools were initiatives by the Canadian government to indoctrinate Indian kids and dismantle their traditional cultures6. Kids have separated from their families, and not so long ago, many unidentified mass graves of kids were found across Canada7,8. They were the cultural genocide victims of residential schools.

The pole has three parts that tell a story5 —starting from the bottom or before residential schools represented by salmon and Bear Mother. The middle part tells the story of residential schools with the school building, children, and spirit figures as the representatives. The top part with a prominent eagle, canoe, longboat, and family show reconciliation between the Canadian government and First Nations.

Besides having art installations in open spaces, there is also the Museum of Anthropology at UBC. Inside the museum, we can find totems, wooden statues, paintings, and traditional tools to make art or for daily use. The art objects come from nature, and the orca is the most popular as it is a sacred animal. Those objects show the reciprocity between humans and nature.

Totem pole and beyond

The government of Canada has openly apologised to former students of Indian residential schools. This action was followed by provincial governments and institutions. In 2018, Santa J. Ono, President and Vice-Chancellor of UBC, also apologised to the community. It also marked the opening of the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre at UBC (IRSHDC). IRSHDC and Reconciliation Pole are more than a building centre or beautiful craftsmanship. Through IRSHDC and Reconciliation Pole, UBC recognises First Nations as the land owner. They ensure the dark history of residential schools will not be forgotten.

Photo credits:

Photo 1: Abdulrahman Shinnawy (used with permission)

Photos 2 & 3: Karina Sasti Prabowo

Created by : Karina Sasti Prabowo

Karina is a final-year Psychology student at Universitas Gadjah Mada who got the opportunity to study at the University of British Columbia for one term. If you can’t find her at home, you’ll find her in the mountains or on the beach with her sweets.

References

1Irwin, R. (2018, September 25). Aboriginal title. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 29, 2022, from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/aboriginal-title

2Wilson, K., & Henderson, J. (2014). First peoples: A guide to newcomers. City of Vancouver.

3Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada; (2021, October 15). First Nations. Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada; Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100013791/1535470872302

4Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. (2011, September 2). A history of treaty-making in Canada. Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Retrieved June 29, 2022, from https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1314977704533/1544620451420

5What is the reconciliation pole? UBC Student Services. (2020, March 5). Retrieved June 29, 2022, from https://students.ubc.ca/ubclife/what-reconciliation-pole

6Miller, J. R. (2012, October 10). Residential schools in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 3, 2022, from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-schools

7 Cecco, L. (2021, July 13). Canada: At least 160 more unmarked graves found in British Columbia. The Guardian. Retrieved July 4, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/jul/13/canada-unmarked-graves-british-columbia-residential-school

8 Paige, P. (2022, May 18). Human remains found near Alberta Residential School site likely children, First Nation says | CBC News. CBCnews. Retrieved July 4, 2022, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/human-remains-found-near-alberta-residential-school-site-likely-children-first-nation-says-1.6457286