Protests, revolutions, and a cry for change would not be considered as novelty in modern society. Come along with Tama as he takes you on a reflective journey about activism through his Insight piece.

When you hear ‘Poland’, what do you imagine? Before I went for IISMA, my brother told me that Poland is a racist and Islamophobic country, while others might say it is a homophobic, anti-immigrant, and Eurosceptic country. Through the people I met during my study, I uncover another complex reality of modern Warsaw and Poland.

Ani Jednej Więcej! (Not one more) were chanted during a pro-choice protest in Warsaw. These words were referring to the first victim of the country’s strict abortion law and to my personal interpretation, a call to end the autocratic turn in the country which has victimized many vulnerable communities and minorities.

I wrote the ‘Polish protest’ as a topic for my final essay and I never thought someday I would join a pro-choice rally in Warsaw in November 2021 by accident. I was walking back home from a museum trip when I stumbled upon the mass of people blocking the street near my university. Not just youth and women, but also men and even the elderly, such as, members of Polish babcie (grandmothers).

During the protest, I talked to a middle-aged woman. I forgot her name, but she spoke English and I remembered every single thing she said to me: “People are going out protesting against strict abortion laws,” and “Women are forced to give birth even though the baby is dead already.” The woman showed me a photo of someone whom she said was as beautiful as an actress “Her name is Izabela,” she continued, “doctors at the hospital held off terminating her pregnancy and risked the mom’s life instead due to the restrictive abortion law.” We then continued marching to the Polish Ministry of Health.

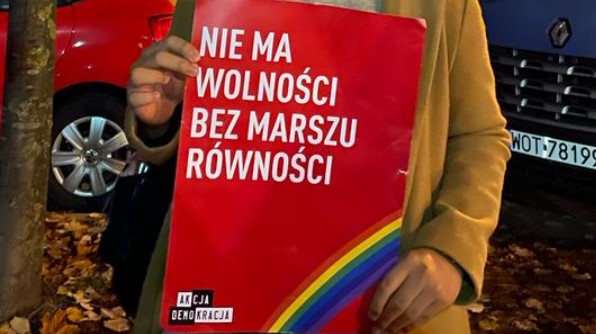

During my exchange program at the University of Warsaw, my IISMA friends and I have witnessed at least five rallies in just one month : three pro-choice rallies on October 23rd, October 30th, and November 6th, an equality rally on October 28th, 2011, and one pro-EU rally on October 11th, 2021. But nonviolence actions did not stop there, as it has been embedded into Polish youth’s daily life. In Warsaw, I saw so many flags, posters, songs, dances, and even daily clothing – people really try to show who they are and speak up about injustice.

My professor, Maciej Raś (2017) explained that the political discourse in modern Poland is a battlefield between conservative right-wing forces and the liberal right with various left-wing politicians and activists aside. Since the dissolution of the Warsaw pact and its accession to the EU in 2004, Poland has gone under drastic transformation into the Western political structure with highly conservative populations. With these sharp socio-cultural differences, several parties have taken various positions from being Euro-enthusiast, Europragmatic, Eurosceptic, and Euroreject (Kopecky, Petr, & Mudde, 2002). Historically, Poland has had been governed by parties from many political spectrums, both from the left or right. We can find political parties in Poland that are generally enthusiasts with more integration with EU structure and values while also finding those that are rejecting not only EU values but also further integration with the EU.

However, since its absolute majority victory in Sejm (legislature) in 2015, Poland is ruled by Law and Justice party or PiS (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość), a right-wing populist and Eurosceptic party. The party’s conservative base dislikes what they see as EU-imposed secularism such as reforms mandated by the Union on gay rights and women’s equality, including abortion laws (Raś, 2017). They tried to impose restrictive abortion rights as well as the establishment of “LGBT-free zones” – which was finally cancelled – and a law introduced by a member of parliament to ban pride parades. I was present in front of the Sejm with everyone who was singing, marching, mocking the politicians, and roleplaying in case the legislation passed. Due to its abortion and anti-LGBTQ+ laws, Poland is now at a standoff with the EU due to its rule of law issue, specifically on the independence of the court and how national laws can take precedence over EU law (DW, 2021a). Fearing Polexit, Poles in 100 towns organized pro-European rallies as Brussels-Warsaw tensions simmer on October, 11th (Al Jazeera, 2021).

Not just women and LGBTQ+, Muslims and refugees of colour are also targets of discrimination, especially by the conservatives. This is evident during the massive securitization (the use of security measures such as pushback and deployment of military personnel) towards mainly Muslim refugees trying to cross the Polish-Belarusian border. In our international migration class, we refer to this merely as an act to “secure the border,” while on the streets of Warsaw, activists are protesting against migrant pushbacks at the Belarusian border (DW, 2021b). In Indonesia, we always focus on the irony as Poland has been selective towards refugees. But this selectivity – despite its harmful impact – is predictable as Poland’s political sphere has been dominated by nationalistic and conservative values, aimed at defending socio-cultural and national values (Raś, 2017).

Poland has been receiving immigrants from Belarus and Ukraine with open arms. At least 3.5 million Ukrainians have fled to Poland since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February as the UN Reported in May 2022. Even before the escalation, we already have a lot of Ukrainian and Belarusian friends. My barber came from Belarus, he talked about how much he despises the (pro-Russia) government, and that he is running away from the country due to the ongoing political crisis. This sentiment was also echoed during the Warsaw Security Forum 2021 where I got to see Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, a leader of the Belarusian government opposition online.

These depict Poland’s hostility towards Russia and its active foreign policy influencing its east neighbourhood (Celewicz & Nizioł-Celewicz, 2006). Their modern nationality was built by a strong feeling against Russia and their past communist history, while at the same time building ties with its eastern neighbours by cultivating similarities in history and socio-cultural values (Raś, 2017).

From the rallies and refugees, I learned that Poland, especially Warsaw, is not only an interesting subject in international relations, but also a vibrant, dynamic, and place of geostrategic significance. Furthermore, their stance on Russia and its reception of Ukrainian refugees puts forward their position in the international arena. Poland was the center of the beginning of World War II, the site of the worst genocide in history, and is now the hotspot for EU-Russia rivalry. Thus, different ideologies exist and at a time one might triumph over the other, but it doesn’t mean that it goes uncontested by other narratives.

As youth and activists go down the street, protesting and demanding change and betterment, people are on their way to defending democracy amidst setbacks as well as avoiding the tendency of the political sphere to be completely dominated by nationalistic and conservative right-wings (Raś, 2017). Dissents among younger populations toward PiS is growing and activists need to be hopeful and sustain the movement. After all, Indonesia is facing similar situations with our deteriorating democracy and political spectrum dominated by nationalists and religious conservatives (Warburton, 2020). Youths and activists in both countries try to avoid further polarization and democratic deconsolidation.

It is reductionist to say that Polish in general is racist, Islamophobic, and anti-immigrant. In fact, Polish is known for hospitality towards guests. The country indeed is currently ruled by a Eurosceptic and conservative right wing-party, but that does not mean that people are not fighting against it. It is too monolithic to say that Poland in general is anti-immigrant and undemocratic. Dharmaputra (2022) moreover mentioned the lack of expertise on the subject of the “Eastern European” (and Post-soviet) region when he addressed Indonesian netizens’ pro-invasion stance on the Russia-Ukraine issues.

When we try to understand post-Soviet and post-communist countries, we often base our understanding on essentialist cold-war paradigms such as Mearsheimer’s blame on the West or Huntington’s infamous Clash of Civilizations, consequently we neglect the political transformation and development in each of the post-Soviet countries. This way, we fail to understand modern Poland, Eastern Europe, and their complexities.

References

Celewicz, M. & Nizioł-Celewicz, M. (2006). UNISCI Discussion Papers No. 10 (Enero), January 2006.

“Death of pregnant woman Izabela in Poland ignites debate about abortion ban, sparks massive protests across the country,” Abc.net. 7 November 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-11-07/death-pregnant-woman-ignites-debate-abortion-ban-poland/100601190

Dharmaputra, R. “Why do so many Indonesians back Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine?” Indonesia at Melbourne, University of Melbourne. 9 March 2022. https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/why-do-so-many-indonesians-back-russias-invasion-of-ukraine/

“EU starts new legal action against Poland over rule of law.” DW. 22 December 2021. https://www.dw.com/en/eu-starts-new-legal-action-against-poland-over-rule-of-law/a-60220102

“Fearing ‘Polexit’, Poles join mass pro-EU rallies.” Al Jazeera. 11 October 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/10/11/polexit-fears-prompt-pro-eu-rallies-across-poland

Kopecky, Petr, and Mudde, C. (2002) The Two Sides of Euroscepticism. Party positions on European integration in East Central Europe. European Union Politics 3(3): 297–326.

“Poland: Thousands protest against migrant pushbacks at Belarus border.” DW. 17 October 2021. https://www.dw.com/en/poland-thousands-protest-against-migrant-pushbacks-at-belarus-border/a-59532143

Raś, M. (2017). “Foreign and Security Policy in the party Discourse in Poland: Main Futures.” Revista UNISCI/UNISCI Journal No. 43 (Enero/January 2017). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/RUNI.54783

“Ukrainian refugees arrive in Poland ‘in a state of distress and anxiety’” United Nations, 27 May 2022, https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/05/1119172

Warburton, E. (2020). “Deepening Polarization and Democratic Decline in Indonesia.” in T. Carothers & A. O’Donohue (Eds.), Political Polarization in South & Southeast Asia: Old Divisions, New Dangers. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Created by : Muhammad Anugrah Utama

Tama is a Bachelor of Political Sciences, majoring in International Relations, at Universitas Gadjah Mada. Tama was an intern at Amnesty International Indonesia and are particularly interested in human security and human rights issues. Through rallies and refugees in daily Warsaw, Tama discovered their passion in research, academics, and activism.